A vaccine is a biological preparation that provides active acquired immunity to a particular disease. A vaccine typically contains an agent that resembles a disease-causing microorganism and is often made from weakened or killed forms of the microbe, its toxins, or one of its surface proteins. The agent stimulates the body's immune system to recognize the agent as a threat, destroy it, and to further recognize and destroy any of the microorganisms associated with that agent that it may encounter in the future. Vaccines can be prophylactic (example: to prevent or ameliorate the effects of a future infection by a natural or "wild" pathogen), or therapeutic (e.g., vaccines against cancer are being investigated).

The administration of vaccines is called vaccination. Vaccination is the most effective method of preventing infectious diseases; widespread immunity due to vaccination is largely responsible for the worldwide eradication of smallpox and the restriction of diseases such as polio, measles, and tetanus from much of the world. The effectiveness of vaccination has been widely studied and verified; for example, vaccines that have proven effective include the influenza vaccine, the HPV vaccine, and the chicken pox vaccine. The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that licensed vaccines are currently available for twenty-five different preventable infections.

The terms vaccine and vaccination are derived from Variolae vaccinae (smallpox of the cow), the term devised by Edward Jenner to denote cowpox. He used it in 1798 in the long title of his Inquiry into the Variolae vaccinae known as the Cow Pox, in which he described the protective effect of cowpox against smallpox. In 1881, to honor Jenner, Louis Pasteur proposed that the terms should be extended to cover the new protective inoculations then being developed.

Effectiveness[]

A child with measles, a vaccine-preventable disease

There is overwhelming scientific consensus that vaccines are a very safe and effective way to fight and eradicate infectious diseases. Limitations to their effectiveness, nevertheless, exist. Sometimes, protection fails because the host's immune system simply does not respond adequately or at all. Lack of response commonly results from clinical factors such as diabetes, steroid use, HIV infection, or age. It also might fail for genetic reasons if the host's immune system includes no strains of B cells that can generate antibodies suited to reacting effectively and binding to the antigens associated with the pathogen.

Even if the host does develop antibodies, protection might not be adequate; immunity might develop too slowly to be effective in time, the antibodies might not disable the pathogen completely, or there might be multiple strains of the pathogen, not all of which are equally susceptible to the immune reaction. However, even a partial, late, or weak immunity, such as a one resulting from cross-immunity to a strain other than the target strain, may mitigate an infection, resulting in a lower mortality rate, lower morbidity, and faster recovery.

Adjuvants commonly are used to boost immune response, particularly for older people (50–75 years and up), whose immune response to a simple vaccine may have weakened.

Maurice Hilleman's measles vaccine is estimated to prevent 1 million deaths every year.

The efficacy or performance of the vaccine is dependent on a number of factors:

- the disease itself (for some diseases vaccination performs better than for others)

- the strain of vaccine (some vaccines are specific to, or at least most effective against, particular strains of the disease)

- whether the vaccination schedule has been properly observed.

- idiosyncratic response to vaccination; some individuals are "non-responders" to certain vaccines, meaning that they do not generate antibodies even after being vaccinated correctly.

- assorted factors such as ethnicity, age, or genetic predisposition.

If a vaccinated individual does develop the disease vaccinated against (breakthrough infection), the disease is likely to be less virulent than in unvaccinated victims.

The following are important considerations in the effectiveness of a vaccination program:

- careful modeling to anticipate the effect that an immunization campaign will have on the epidemiology of the disease in the medium to long term

- ongoing surveillance for the relevant disease following introduction of a new vaccine

- maintenance of high immunization rates, even when a disease has become rare.

In 1958, there were 763,094 cases of measles in the United States; 552 deaths resulted. After the introduction of new vaccines, the number of cases dropped to fewer than 150 per year (median of 56). In early 2008, there were 64 suspected cases of measles. Fifty-four of those infections were associated with importation from another country, although only 13% were actually acquired outside the United States; 63 of the 64 individuals either had never been vaccinated against measles or were uncertain whether they had been vaccinated.

Vaccines led to the eradication of smallpox, one of the most contagious and deadly diseases in humans. Other diseases such as rubella, polio, measles, mumps, chickenpox, and typhoid are nowhere near as common as they were a hundred years ago thanks to widespread vaccination programs. As long as the vast majority of people are vaccinated, it is much more difficult for an outbreak of disease to occur, let alone spread. This effect is called herd immunity. Polio, which is transmitted only between humans, is targeted by an extensive eradication campaign that has seen endemic polio restricted to only parts of three countries (Afghanistan, Nigeria, and Pakistan). However, the difficulty of reaching all children as well as cultural misunderstandings have caused the anticipated eradication date to be missed several times.

Vaccines also help prevent the development of antibiotic resistance. For example, by greatly reducing the incidence of pneumonia caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae, vaccine programs have greatly reduced the prevalence of infections resistant to penicillin or other first-line antibiotics.

Adverse effects[]

Vaccination given during childhood is generally safe. Adverse effects, if any, are generally mild. The rate of side effects depends on the vaccine in question. Some common side effects include fever, pain around the injection site, and muscle aches. Additionally, some individuals may be allergic to ingredients in the vaccine. MMR vaccine is rarely associated with febrile seizures.

Severe side effects are extremely rare. Varicella vaccine is rarely associated with complications in immunodeficient individuals and rotavirus vaccines are moderately associated with intussusception.

Some countries such as the United Kingdom provide compensation for victims of severe adverse effects via its Vaccine Damage Payment. The United States has the National Childhood Vaccine Injury Act. At least 19 countries have such no-fault compensation.

Types[]

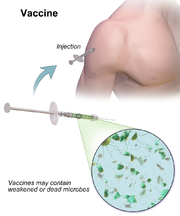

Vaccine

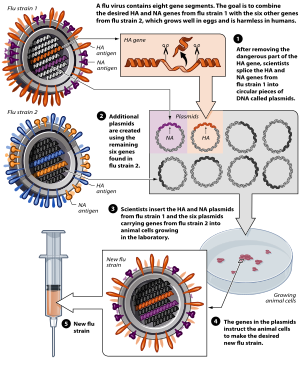

Avian flu vaccine development by reverse genetics techniques.

Vaccines are dead or inactivated organisms or purified products derived from them.

There are several types of vaccines in use. These represent different strategies used to try to reduce the risk of illness while retaining the ability to induce a beneficial immune response.

Inactivated[]

- Main articles: Inactivated vaccine

Some vaccines contain inactivated, but previously virulent, micro-organisms that have been destroyed with chemicals, heat, or radiation. Examples include the polio vaccine, hepatitis A vaccine, rabies vaccine and some influenza vaccines.

Attenuated[]

- Main articles: Attenuated vaccine

Some vaccines contain live, attenuated microorganisms. Many of these are active viruses that have been cultivated under conditions that disable their virulent properties, or that use closely related but less dangerous organisms to produce a broad immune response. Although most attenuated vaccines are viral, some are bacterial in nature. Examples include the viral diseases yellow fever, measles, mumps, and rubella, and the bacterial disease typhoid. The live Mycobacterium tuberculosis vaccine developed by Calmette and Guérin is not made of a contagious strain but contains a virulently modified strain called "BCG" used to elicit an immune response to the vaccine. The live attenuated vaccine containing strain Yersinia pestis EV is used for plague immunization. Attenuated vaccines have some advantages and disadvantages. They typically provoke more durable immunological responses and are the preferred type for healthy adults. But they may not be safe for use in immunocompromised individuals, and on rare occasions mutate to a virulent form and cause disease.

Toxoid[]

Toxoid vaccines are made from inactivated toxic compounds that cause illness rather than the micro-organism. Examples of toxoid-based vaccines include tetanus and diphtheria. Toxoid vaccines are known for their efficacy. Not all toxoids are for micro-organisms; for example, Crotalus atrox toxoid is used to vaccinate dogs against rattlesnake bites.

Subunit[]

Protein subunit – rather than introducing an inactivated or attenuated micro-organism to an immune system (which would constitute a "whole-agent" vaccine), a fragment of it can create an immune response. Examples include the subunit vaccine against Hepatitis B virus that is composed of only the surface proteins of the virus (previously extracted from the blood serum of chronically infected patients, but now produced by recombination of the viral genes into yeast) or as an edible algae vaccine, the virus-like particle (VLP) vaccine against human papillomavirus (HPV) that is composed of the viral major capsid protein, and the hemagglutinin and neuraminidase subunits of the influenza virus. Subunit vaccine is being used for plague immunization.

Conjugate[]

Conjugate – certain bacteria have polysaccharide outer coats that are poorly immunogenic. By linking these outer coats to proteins (e.g., toxins), the immune system can be led to recognize the polysaccharide as if it were a protein antigen. This approach is used in the Haemophilus influenzae type B vaccine.

Experimental[]

Electroporation System for experimental "DNA vaccine" delivery

A number of innovative vaccines are also in development and in use:

- Dendritic cell vaccines combine dendritic cells with antigens in order to present the antigens to the body's white blood cells, thus stimulating an immune reaction. These vaccines have shown some positive preliminary results for treating brain tumors and are also tested in malignant melanoma.

- Recombinant vector – by combining the physiology of one micro-organism and the DNA of another, immunity can be created against diseases that have complex infection processes. An example is the RVSV-ZEBOV vaccine licensed to Merck that is being used in 2018 to combat ebola in Congo.

- DNA vaccination – an alternative, experimental approach to vaccination called DNA vaccination, created from an infectious agent's DNA, is under development. The proposed mechanism is the insertion (and expression, enhanced by the use of electroporation, triggering immune system recognition) of viral or bacterial DNA into human or animal cells. Some cells of the immune system that recognize the proteins expressed will mount an attack against these proteins and cells expressing them. Because these cells live for a very long time, if the pathogen that normally expresses these proteins is encountered at a later time, they will be attacked instantly by the immune system. One potential advantage of DNA vaccines is that they are very easy to produce and store. As of 2015, DNA vaccination is still experimental and is not approved for human use.

- T-cell receptor peptide vaccines are under development for several diseases using models of Valley Fever, stomatitis, and atopic dermatitis. These peptides have been shown to modulate cytokine production and improve cell-mediated immunity.

- Targeting of identified bacterial proteins that are involved in complement inhibition would neutralize the key bacterial virulence mechanism.

While most vaccines are created using inactivated or attenuated compounds from micro-organisms, synthetic vaccines are composed mainly or wholly of synthetic peptides, carbohydrates, or antigens.

Valence[]

Vaccines may be monovalent (also called univalent) or multivalent (also called polyvalent). A monovalent vaccine is designed to immunize against a single antigen or single microorganism. A multivalent or polyvalent vaccine is designed to immunize against two or more strains of the same microorganism, or against two or more microorganisms. The valency of a multivalent vaccine may be denoted with a Greek or Latin prefix (e.g., tetravalent or quadrivalent). In certain cases, a monovalent vaccine may be preferable for rapidly developing a strong immune response.

Heterotypic[]

Also known as heterologous or "Jennerian" vaccines, these are vaccines that are pathogens of other animals that either do not cause disease or cause mild disease in the organism being treated. The classic example is Jenner's use of cowpox to protect against smallpox. A current example is the use of BCG vaccine made from Mycobacterium bovis to protect against human tuberculosis.

Developing immunity[]

The immune system recognizes vaccine agents as foreign, destroys them, and "remembers" them. When the virulent version of an agent is encountered, the body recognizes the protein coat on the virus, and thus is prepared to respond, by (1) neutralizing the target agent before it can enter cells, and (2) recognizing and destroying infected cells before that agent can multiply to vast numbers.

When two or more vaccines are mixed together in the same formulation, the two vaccines can interfere. This most frequently occurs with live attenuated vaccines, where one of the vaccine components is more robust than the others and suppresses the growth and immune response to the other components. This phenomenon was first noted in the trivalent Sabin polio vaccine, where the amount of serotype 2 virus in the vaccine had to be reduced to stop it from interfering with the "take" of the serotype 1 and 3 viruses in the vaccine. This phenomenon has also been found to be a problem with the dengue vaccines currently being researched, where the DEN-3 serotype was found to predominate and suppress the response to DEN-1, -2 and -4 serotypes.

Adjuvants and preservatives[]

Vaccines typically contain one or more adjuvants, used to boost the immune response. Tetanus toxoid, for instance, is usually adsorbed onto alum. This presents the antigen in such a way as to produce a greater action than the simple aqueous tetanus toxoid. People who have an adverse reaction to adsorbed tetanus toxoid may be given the simple vaccine when the time comes for a booster.

In the preparation for the 1990 Persian Gulf campaign, whole cell pertussis vaccine was used as an adjuvant for anthrax vaccine. This produces a more rapid immune response than giving only the anthrax vaccine, which is of some benefit if exposure might be imminent.

Vaccines may also contain preservatives to prevent contamination with bacteria or fungi. Until recent years, the preservative thimerosal was used in many vaccines that did not contain live virus. As of 2005, the only childhood vaccine in the U.S. that contains thimerosal in greater than trace amounts is the influenza vaccine, which is currently recommended only for children with certain risk factors. Single-dose influenza vaccines supplied in the UK do not list thiomersal (its UK name) in the ingredients. Preservatives may be used at various stages of production of vaccines, and the most sophisticated methods of measurement might detect traces of them in the finished product, as they may in the environment and population as a whole.

Schedule[]

- Main articles: Vaccination schedule

- For country-specific information on vaccination policies and practices, see: Vaccination policy

In order to provide the best protection, children are recommended to receive vaccinations as soon as their immune systems are sufficiently developed to respond to particular vaccines, with additional "booster" shots often required to achieve "full immunity". This has led to the development of complex vaccination schedules. In the United States, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, which recommends schedule additions for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, recommends routine vaccination of children against: hepatitis A, hepatitis B, polio, mumps, measles, rubella, diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, HiB, chickenpox, rotavirus, influenza, meningococcal disease and pneumonia. A large number of vaccines and boosters recommended (up to 24 injections by age two) has led to problems with achieving full compliance. In order to combat declining compliance rates, various notification systems have been instituted and a number of combination injections are now marketed (e.g., Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and MMRV vaccine), which provide protection against multiple diseases.

Besides recommendations for infant vaccinations and boosters, many specific vaccines are recommended for other ages or for repeated injections throughout life—most commonly for measles, tetanus, influenza, and pneumonia. Pregnant women are often screened for continued resistance to rubella. The human papillomavirus vaccine is recommended in the U.S. (as of 2011) and UK (as of 2009). Vaccine recommendations for the elderly concentrate on pneumonia and influenza, which are more deadly to that group. In 2006, a vaccine was introduced against shingles, a disease caused by the chickenpox virus, which usually affects the elderly.

Production[]

Two workers make openings in chicken eggs in preparation for production of measles vaccine.

Vaccine production has several stages. First, the antigen itself is generated. Viruses are grown either on primary cells such as chicken eggs (e.g., for influenza) or on continuous cell lines such as cultured human cells (e.g., for hepatitis A). Bacteria are grown in bioreactors (e.g., Haemophilus influenzae type b). Likewise, a recombinant protein derived from the viruses or bacteria can be generated in yeast, bacteria, or cell cultures. After the antigen is generated, it is isolated from the cells used to generate it. A virus may need to be inactivated, possibly with no further purification required. Recombinant proteins need many operations involving ultrafiltration and column chromatography. Finally, the vaccine is formulated by adding adjuvant, stabilizers, and preservatives as needed. The adjuvant enhances the immune response of the antigen, stabilizers increase the storage life, and preservatives allow the use of multidose vials. Combination vaccines are harder to develop and produce, because of potential incompatibilities and interactions among the antigens and other ingredients involved.

Vaccine production techniques are evolving. Cultured mammalian cells are expected to become increasingly important, compared to conventional options such as chicken eggs, due to greater productivity and low incidence of problems with contamination. Recombination technology that produces genetically detoxified vaccine is expected to grow in popularity for the production of bacterial vaccines that use toxoids. Combination vaccines are expected to reduce the quantities of antigens they contain, and thereby decrease undesirable interactions, by using pathogen-associated molecular patterns.

In 2010, India produced 60 percent of the world's vaccine worth about $900 million(€670 million).

Excipients[]

Beside the active vaccine itself, the following excipients and residual manufacturing compounds are present or may be present in vaccine preparations:

- Aluminum salts or gels are added as adjuvants. Adjuvants are added to promote an earlier, more potent response, and more persistent immune response to the vaccine; they allow for a lower vaccine dosage.

- Antibiotics are added to some vaccines to prevent the growth of bacteria during production and storage of the vaccine.

- Egg protein is present in influenza and yellow fever vaccines as they are prepared using chicken eggs. Other proteins may be present.

- Formaldehyde is used to inactivate bacterial products for toxoid vaccines. Formaldehyde is also used to inactivate unwanted viruses and kill bacteria that might contaminate the vaccine during production.

- Monosodium glutamate (MSG) and 2-phenoxyethanol are used as stabilizers in a few vaccines to help the vaccine remain unchanged when the vaccine is exposed to heat, light, acidity, or humidity.

- Thimerosal is a mercury-containing antimicrobial that is added to vials of vaccine that contain more than one dose to prevent contamination and growth of potentially harmful bacteria. Due to the controversy surrounding thimerosal it has been removed from most vaccines except multi-use influenza, where it was reduced to levels so that a single dose contained less than 1 microgram of mercury, a level similar to eating 10g of canned tuna.

Role of preservatives[]

Many vaccines need preservatives to prevent serious adverse effects such as Staphylococcus infection, which in one 1928 incident killed 12 of 21 children inoculated with a diphtheria vaccine that lacked a preservative. Several preservatives are available, including thiomersal, phenoxyethanol, and formaldehyde. Thiomersal is more effective against bacteria, has a better shelf-life, and improves vaccine stability, potency, and safety; but, in the U.S., the European Union, and a few other affluent countries, it is no longer used as a preservative in childhood vaccines, as a precautionary measure due to its mercury content. Although controversial claims have been made that thiomersal contributes to autism, no convincing scientific evidence supports these claims. Furthermore, a 10–11 year study of 657,461 children found that the MMR vaccine does not cause autism and actually reduced the risk of autism by 7 percent.

Veterinary medicine[]

Goat vaccination against sheep pox and pleural pneumonia

Vaccinations of animals are used both to prevent their contracting diseases and to prevent transmission of disease to humans. Both animals kept as pets and animals raised as livestock are routinely vaccinated. In some instances, wild populations may be vaccinated. This is sometimes accomplished with vaccine-laced food spread in a disease-prone area and has been used to attempt to control rabies in raccoons.

Where rabies occurs, rabies vaccination of dogs may be required by law. Other canine vaccines include canine distemper, canine parvovirus, infectious canine hepatitis, adenovirus-2, leptospirosis, bordatella, canine parainfluenza virus, and Lyme disease, among others.

Cases of veterinary vaccines used in humans have been documented, whether intentional or accidental, with some cases of resultant illness, most notably with brucellosis. However, the reporting of such cases is rare and very little has been studied about the safety and results of such practices. With the advent of aerosol vaccination in veterinary clinics for companion animals, human exposure to pathogens that are not naturally carried in humans, such as Bordetella bronchiseptica, has likely increased in recent years. In some cases, most notably rabies, the parallel veterinary vaccine against a pathogen may be as much as orders of magnitude more economical than the human one.

References[]

|

This page uses content that though originally imported from the Wikipedia article Vaccine might have been very heavily modified, perhaps even to the point of disagreeing completely with the original wikipedia article. The list of authors can be seen in the page history. The text of Wikipedia is available under the Creative Commons Licence. |